Algorithms with Python - Merge Sort and Tim Sort

Overview

Continuing on our journey to explore sorting algorithms with Python, we will talk about the following in our Part 2 of the Sorting Algorithms w/ Python series.

- Merge Sort

- Tim Sort

Links to Other Parts of Series

Array Sorting Complexities

Recall the time complexities (for a full summary, see Part 1).

| Algorithm | Time Complexity | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Best | Average | Worst | |

| Merge Sort | Ω(nlog(n)) | θ(nlog(n)) | O(nlog(n)) |

| Tim Sort | Ω(n) | θ(nlog(n)) | O(nlog(n)) |

Note that compared to the algorithms we’ve talked about in Part 1, these algorithms has better time complexity properties. We will explain how that is achieved.

Sorting Algorithms

Merge Sort

|

|---|

| (gif Credit) |

Merge sort is a classic “divide and conquer” algorithm, where we split up the list that needs to be sorted, sort them in small batches, then put them back together in order. In particular, the first step is to divide all elements into single elements, then combine into pairs, sort the pair, then combine into 4-element batches, and so on, until we have a sorted list.

Python Implementation

# merge sort

def merge_sort(to_sort):

"""

Given a list of integers,

sorts it into ascending order with Merge Sort

(in place)

and returns the sorted list

"""

# length of array to sort

list_len = len(to_sort)

if list_len > 1:

mid = list_len // 2

L = to_sort[:mid]

R = to_sort[mid:]

# here we recursively incur the mergesort function

# The effect is that it will first divide up the

# entire list into individual bits.

# Notice that merge_sort(single element) does nothing

# so that when we reach merge_sort of 2 elements

# we can finally go beyond this point

merge_sort(L)

merge_sort(R)

# Once all elements are divided through the recursive calls

# The function call can finally reach these later codes

# i: index of element we are looking at in list L

# j: index of element we are looking at in list R

# k: total comparisons made / elements saved into arr

i = j = k = 0

# now we look at each list L and R

# starting from the smaller elements (left)

while i < len(L) and j < len(R):

# if element from L is smaller than

# element from R, we pop off the element from L

# save it to our array

# and move on to the next element in L

if L[i] < R[j]:

to_sort[k] = L[i]

i += 1

# similarly the case if the element in R is larger

else:

to_sort[k] = R[j]

j += 1

k += 1

# Checking if any element was left

# when one of the list L or R has been exhausted

# If so, all elements left are larger than the rest.

# if i < len(L): R is exhausted.

# save all remaining elements from L into arr

while i < len(L):

to_sort[k] = L[i]

i += 1

k += 1

# similarly the opposite case

while j < len(R):

to_sort[k] = R[j]

j += 1

k += 1

return to_sort

Now let’s test the code:

# generate some random integers

import random

to_sort = random.sample(range(1, 1000), 20)

to_sort

# [61, 309, 414, 688, 123, 669, 473, 845, 330, 231, 173, 758, 797, 374, 511, 20, 28, 958, 196, 25]

insertion_sort(to_sort)

# [20, 25, 28, 61, 123, 173, 196, 231, 309, 330, 374, 414, 473, 511, 669, 688, 758, 797, 845, 958]

Time Complexity

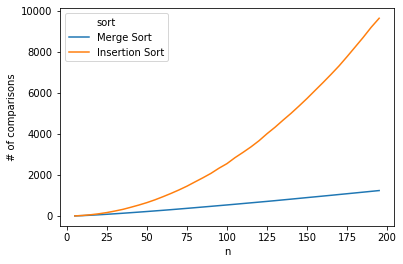

Regardless of the initial condition of the list, Merge Sort always divide and conquers. Within each level of division, the number of comparisons required is on the order of n (n/2 for last level, n/2 to 3n/4 for second to last level, etc.), and the number of levels are of order log(n), since 2# of levels is on the order of n. To show how stark the difference this is from the quadratic time complexities, the # of comparisons is plotted below for merge sort and insertion sort:

As we can see, as the length of the list increases, the big-O difference really starts to reveal itself, where the # of comparisons required for insertion sort simply takes off.

Tim Sort

Tim sort was created in 2001 for implementations of sorting functionalities in Python. It is real-world focused, takes advantage of the superior performance of insertion sort on smaller lists in real-world data where consecutive ordered elements are often present, and the ability of merge sort to combine sorted sub-lists into one final sorted list. The actual implementation has more details, but the implementation below should give us a feel of the inner workings.

Python Implementation

# tim sort

# Adapted from https://gist.github.com/nandajavarma/a3a6b62f34e74ec4c31674934327bbd3

# custom binary search

def binary_search(arr, item, start, end):

"""

This is a recursive implementation of

searching for the correct position of an `item`

in a sorted array `arr`

using binary search technique.

The item may or may not be present in arr.

start / end are specified for recursive calls.

Initial call would specify them as start / end of

arr, respectively. i.e.

start = 0

end = len(arr) - 1

"""

# first specify end game

# if the two pointers meet,

# it means we are done searching.

# and we need to determine the final index

if start == end:

if arr[start] > item:

# item should be inserted to the left of start

return start

else:

# item should be inserted to the right of start

return start + 1

# if we arrive at this state without finding the location

# ((start + end) // 2 is within 1 of end)

# and start != end --> start == end - 1

# it means that start is the correct location

if start > end:

return start

mid = (start + end) // 2

# if item is larger, search in upper half

if arr[mid] < item:

return binary_search(arr, item, mid + 1, end)

# else, search in lower half

elif arr[mid] > item:

return binary_search(arr, item, start, mid - 1)

else:

return mid

# insertion part

def insertion_sort(to_sort):

"""

Given a list of integers,

sorts it into ascending order with Insertion Sort

(done in place)

and returns the sorted list

"""

# length of array to sort

list_len = len(to_sort)

# for each pass, the elements to its left

# is already sorted, and we need to insert

# element i into the correct location

for i in range(1, list_len):

# element in question

el = to_sort[i]

# keep track of where to insert el

shift_count = 0

# start comparing from right to left

# so that we can easily replace in place

for j in range(i-1, -1, -1):

if to_sort[j] > el:

# for all elements larger than el

# shift it 1 index to the right

to_sort[j+1] = to_sort[j]

# el needs to shift 1 more unit to the left

shift_count += 1

else:

# once we hit an element not larger than el

# we can terminate the process, since the rest

# is all going to be smaller

break

# insert el

to_sort[i-shift_count] = el

return to_sort

def merge(left, right):

"""

Takes two sorted lists and returns a single sorted list by comparing the

elements one at a time.

For detailed explanation of the logic, see Part 1

where merge_sort is explained and implemented

"""

if not left:

return right

if not right:

return left

if left[0] < right[0]:

return [left[0]] + merge(left[1:], right)

return [right[0]] + merge(left, right[1:])

# putting together

def timsort(to_sort):

# timsort uses a concept called "runs"

# where consecutive elements in order will be

# put into a run and merged together.

# The actual timsort is more advacned in constructing the

# runs, but the code below suffices to illustrate the logic.

runs, sorted_runs = [], []

l = len(to_sort)

new_run = [to_sort[0]]

for i in range(1, l):

# if last element

if i == l-1:

# append to new run, and add new run to all runs

new_run.append(to_sort[i])

runs.append(new_run)

break

# if next element is larger then current

# i.e. is not in order

if to_sort[i] < to_sort[i-1]:

# if current run is empty

if not new_run:

# append a singleton list to the runs

# and append next element to new run

runs.append([to_sort[i-1]])

new_run.append(to_sort[i])

# if we have a non-empty run

else:

# append the run to the list of runs

runs.append(new_run)

# start new empty run

new_run = []

# if in order, just add next element to current run

else:

new_run.append(to_sort[i])

# Note that our implementation of the "runs"

# actually results in already sorted runs

# such that this insertion_sort step is redeundant.

# However, in a more sophisticated setup, the "runs"

# would not be completey sorted, but would comtain

# some bits of unsorted data, and truncated to make sure

# each run is of specified length (or shorter),

# where insertion sort performs best

for each in runs:

# use insertion sort to sort each run,

# and append to sorted_runs to keep track

sorted_runs.append(insertion_sort(each))

sorted_array = []

for run in sorted_runs:

# finally, for each of these sorted runs

# we merge them together

sorted_array = merge(sorted_array, run)

return sorted_array

Time Complexity

In best case scenario, where the list is already sorted, the run-construction, insertion sort, and merging part each takes linear time. Hence a big-) of n. Average case and worst case is bounded by merge sort’s nlog(n) complexity.

Leave a comment